Clik here to view.

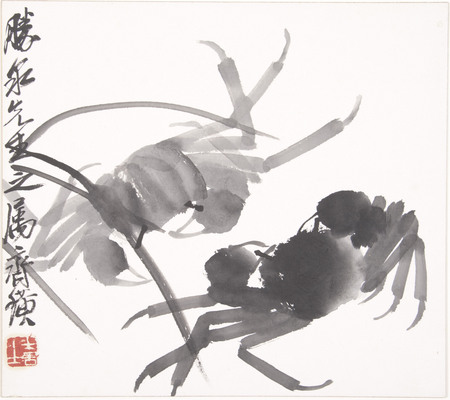

"Crabs" by Qi Baishi

Organized in partnership with New York City’s Noguchi Museum, the exhibit has been mounted in the UMMA’s spacious A. Alfred Taubman Gallery. consists of approximately 60 drawings (including ink paintings and calligraphic works), sculpture, artist’s tools, and other interpretive materials drawn from the UMMA, the Noguchi Museum, and other public and private art collections.

Shedding “new light on the transformative relationship between American sculptor Isamu Noguchi (1904-88) and Chinese ink painter Qi Baishi (1864-1957),” as the UMMA’s press release tells us, “Isamu Noguchi/Qi Baishi/Beijing 1930” (which will be on view in Long Island City and Seattle following its Ann Arbor premiere) handsomely drapes the UMMA’s second floor prime exhibition space with an assurance that’s as inspiring as it is magnificent.

This is not only because the art on display is superior. Nor is the exhibit merely an example of an acolyte following the influence of his master — because the relationship between these two talents was all too brief. Rather, the exhibit’s strength resides in how much influence one superior talent can impart to another superior talent through what was an exceedingly short period of time.

Qi Baishi (1864-1957) was one of China’s revered 20th century artists whose calligraphy, landscape, and animal paintings were crafted in an economic style with characteristic whimsy reflecting common Chinese cultural values. Originally self-taught due to his family’s impoverished circumstance, Qi eventually incorporated a reverence for fine brushwork and meticulous detail into a style of art that’s always been the highest tradition of Sino aesthetic.

Isamu Noguchi (1904-88) had a six-decade career as a sculptor, landscape architect, stage designer for Martha Graham, and furniture designer; his influence is still felt keenly today. The son of Japanese poet Yone Noguchi and his American translator Leone Gilmour, Isamu Noguchi opted for a career in art that took him around the world with teachers that included Gutzon Borglum (creator of the Mount Rushmore National Memorial) and biomorphic abstractionist sculptor Constantin Brancusi.

“Isamu Noguchi/Qi Baishi/Beijing 1930” heartily illustrates the six-month influence this Chinese master had on this young American, who rapidly absorbed the older man’s style and knowledge. The Noguchi drawings that came from this encounter were to be atypical of his future work, but Qi’s impact had a profound effect on his creativity.

As exhibition organizer UMMA Associate Curator of Asian Art Natsu Oyobe tells us in her introduction, Noguchi’s work “has long been associated with Japan. Indeed his introduction to ancient sculpture and garden design traditions during a stay in Japan in 1931 is thought of as a turning point in his early career.

“Less well known is the story of Noguchi’s six transformative months in Beijing (formerly known as Peking); from July 1930 to January 1931. There, Sotokichi Katsuizumi (1889-1985), a Japanese businessman and collector of Chinese painting, introduced him to Qi Baishi.

“Noguchi spoke no Chinese and Qi no English, but they quickly formed a friendship and Noguchi began to study with the master ink painter. Under Qi’s influence, he took up brush, ink, and paper — the key tools of East Asian traditional painting and calligraphy — to create the series of more than one hundred works later called the ‘Peking Drawings.’

“Seen together as a group and alongside examples of Qi’s paintings — as they are for the first time in this exhibition — these impressive works suggest the importance of China in Noguchi’s artistic formation, usually eclipsed by his relationship to Japan. Indeed the often overlooked ‘Peking Drawings’ acted as a laboratory in which he discovered a language of abstraction that informed his entire career.”

Oyobe is certainly spot on with her observation that Qi had a major impact on Noguchi’s work. For what is on display with these “Peking Drawings” is more than proof enough — just as six months is a remarkably brief period of time for such a sustained impact.

As Oyobe tells us, Qi’s traditionalist style of art was well established by the time he was introduced to Noguchi. Indeed, “Noguchi began his exploration of the ancient art of Chinese ink and brush painting by carefully observing Qi’s extraordinary technique, which allowed him to control the flow of ink to produce in a single stroke, dynamic lines of varying thickness and length and to create subtle shading. Noguchi then applied these lessons in his own drawings, freely experimenting with brushstrokes on large sheets of paper laid on a table or floor.”

And as she later adds, Qi’s “highly abbreviated brushwork, rich ink effects, and unusual compositions lifted these subjects to the heights of literati art and made this highly refined and intellectualized tradition accessible to a larger audience. The unique vision Qi brought to his lively depictions of the natural world opened new horizons of expression for Chinese painting and had a major influence on future generations of painters.”

Take one example of Qi’s painting in the exhibit, circa 1930’s album leaf, ink on paper “Crabs.” This masterly painting consists of a series of overlapping lines of varying thickness where Qi’s control of his brush commands a deft interpretation of two crustaceans dramatically facing off one another. Structuring his painting diagonally, Qi crafts a respectful anatomical rendering, but he simultaneously creates far more than a mere likeness. What he creates through his adroit line is a life rendering of these arthropods that we might anticipate at a privileged observational moment.

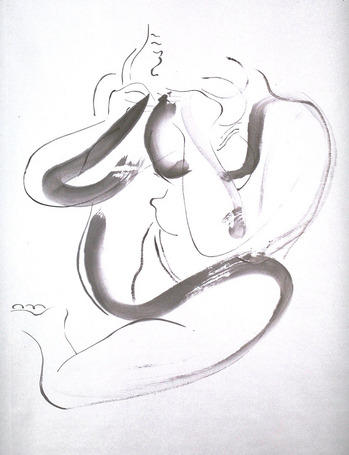

On the other hand, Oyobe tells us that Noguchi was somewhat of a willful student through this six month period and his artistic independence is clearly at hand in the works he produced at this time. “Noguchi neither imitated Qi’s style nor adopted his wide-ranging subject matter. Instead, setting forth on his own path, he focused exclusively on the human body, using the traditional techniques of ink and brush painting to depict the live models his servant found in the streets of Beijing — men, women, children, and mothers with babies, usually nude, that Noguchi posed in every imaginable way.”

Clik here to view.

"Seated Female Nude" by Isamu Noguchi

As can been seen through the many “Peking Drawings” on display, Noguchi’s line is sure even as it’s more immediately expressive and erotic than his teacher’s line. In fact, the most powerful element of Noguchi’s drawings is the certitude of his burgeoning talent. It might seem a wisdom beyond his years; although it’s also certain from the results that he’d already packed a lifetime of worldliness going into his third decade.

We’re told by the exhibit’s gallery tags that Noguchi’s drawings during this period “acted as a laboratory in which he discovered a language of abstraction that informed his entire career.”

And as Oyobe further adds, “Across these diverse works, Noguchi exploits the brush’s potential for creating lines that vary according to the slightest movement and pressure of the artist’s hands and body. In turn, these gently or dynamically undulating brushstrokes both convey the softness of the bodies themselves and highlight the emotional states depicted with great tenderness by the artist.”

This is certainly the case as his sensitivity depicts the enduring bond of maternal love in the many paintings he makes of mother and child. Likewise, his nudes mirror his teacher’s ability to create an immediacy that’s elemental enough to depict a heightened sense of reality while also leave room for emotive exploration.

“While drawing was never again central to Noguchi’s practice,” Oyobe says, “the discoveries that he made with ink and brush in Beijing would bear fruit in his three-dimensional works, whether in metal, stone, clay, earth, or wood. The sweeping brush lines of the “Peking Drawings” are found in his abstract figure sculptures from the mid-1930s and the broad brush strokes so suggestive of both movement and volume in the drawings would emerge as fully three-dimensional forms in his postwar sculpture and garden designs.”

Such a powerful almost subliminal impact in so brief a period of time makes “Isamu Noguchi/Qi Baishi/Beijing 1930” among the rarest of great art displays. It’s as close to a case of aesthetic transference — as well as cultivation of first-rank genius — as we’re likely ever to see through the guise of simple geometry.

“Isamu Noguchi/Qi Baishi/Beijing 1930” will continue through Sept. 1 at the University of Michigan Museum of Art, 525 S. State St. Museum hours are 11 a.m. to 5 p.m. Tuesday-Saturday, and noon to 5 p.m. Sunday. For information, call 734-764-0395.